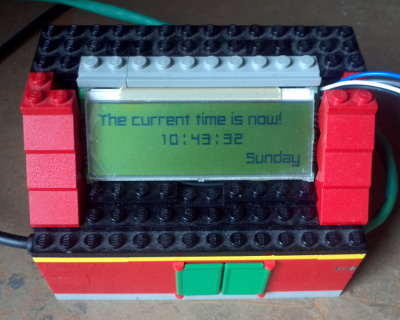

A year or two ago I connected a small 132x32 pixel LCD display to one of my

Raspberry Pis. The idea behind it was that I could use it to display small

status updates or anything else I wanted. Mostly from that aspect it ended up

being a clock.

Once I got some code written for text, my next thought was "could I do video?"

There were a few hurdles there to overcome as well. Codec? Framerate? I ended

making up a solution where I read in 2-bit (black and white) bitmap image and

displayed it. Repeat 24 times a second and you have video.

I noticed something interesting though, in that I could push out images a lot

faster than 24 FPS. I could reach just over the 120 FPS. This is the magic

number for what's known as

active 3D TV. In

Active 3D, the special glasses effectively blank out one eye than the other

rapidly. At the same time the TV is showing the left eye, right, left, right,

etc., at the same speed. (3D in movie theatres, for example

RealD 3D, typically uses

polarized light.)

There are two ways that active glasses are controlled by TVs. The first,

impractical way is radio. Typically Bluetooth. The other way, which fits right

in the realm of hacker electronics, is Infrared. (Just like a remote control!)

Knowing this then I needed a was an infrared transmission from the Pi to the

glasses, and then to match this up with the software I'd already written to

display video. The latter, is easy. The former, not so much so.

The first stumbling block is the infrared transmission signal. Like a remote

control, it's also a specially coded signal. And like for TVs, many makers

have different signals for their glasses. Fortunately, someone has already

made an

analysis of the different signals using an oscilloscope. I managed to find a

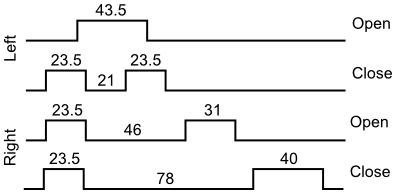

reasonably priced pair of nVidia 3D glases. The protocol for them looks like

this:

Unfortunately the timing of those infrared pulses is in microseconds. This is

a small problem. The Pi can't consistently execute code at microsecond timing.

Millisecond's about the best it can do because Raspbian isn't what's called a

Real-time operating

system. It spends a lot of time instead cycling between different tasks, any

of which can call for CPU time at any moment and interrupting whatever else is

happening.

In a real-time situation like sending a infrared signal, we can't have the

kernel deciding to take a pause in the middle to do something else.

Fortunately, most microcontrollers are real-time, and so will do exactly

what you tell them to in the order you tell them to.

More Than User used an attiny45 to create an infrared remote. I haven't got

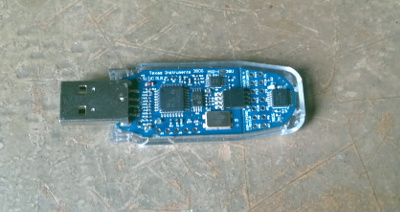

one of those, but I do have a

EZ430-F2013 which is this crazy TI micro-controller in a USB stick format

thing.

The EZ430 is very nice in that it comes with a proper development environment

and a "let's blink the LED" code example—blinking an Infrared LED is what I

wanted to do after all! What I really needed to do then was to learn how to

control blink timing precisely. Things now get a little technical.

Microcontroller programming isn't exactly easy and this was new ground for me.

Eventually I learned that the EZ430 has an onboard 8 MHz clock crystal. What's

neat about this is that you can do something called a timer interrupt. There

are different ways to go about it, but in general in this case I tell the

EZ430 to count down from X to 0, which X is the number of clock ticks. If I

could put in the number 8,000,000 for X, I'd have an exact timing of 1 second.

It's not quite that easy though. The counter is only a 16-bit integer which

means I can only count down from 32,767. Fortunately there are clock dividers

available which let you tweak it around. The catch here is that the protocol

has halfmicrosecond timing. That means I can't divide down directly to 1

MHz timing, and instead can only divide down to 2 MHz timing. My counter then

has to be twice the numbers shown in the protocol diagram.

// set up the timer

DCOCTL = CALDCO_8MHZ;

BCSCTL1 = CALBC1_8MHZ;

BCSCTL2 |= DIVS_2; // divide by 4

TACTL = TASSEL_2 + MC_1 + ID_0;

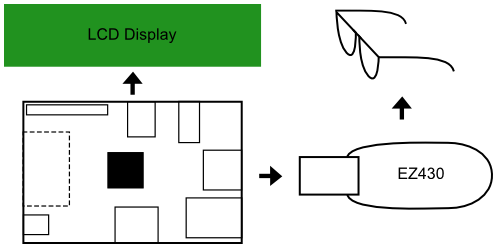

At this point I could control the glasses! I was thrilled! The next challenge

then arrises: connecting this to the Pi. Enter input pin interrupts. The

EZ430 has 8 digital input/output pins. One of them is used as an output for

the infrared LED to talk to the glasses. Another pin I changed to an input,

and then enabled a rising edge interrupt on it. This means as soon as voltage

at the pin is detected it triggers a code call. From this I can then start the

timer and open one eye and close the other.

// setup interrupt on pin 3

P1IE = BIT3;

P1IES &= ~BIT3; // rising edge

_EINT();

Hurrah! I connect the input pin on the EZ430 to a GPIO output from the Pi and

I have glasses control. Now in my video program after a frame is drawn I simply

turn the connected GPIO pin on and off again, triggering an interrupt on the

EZ430, which ends up sending an infred signal to the glasses. Gives a very good

feeling. It may have taken 10 minutes to read this far but it took hours to

learn what I needed on the EZ430 on work it all out.

Unfortunately, my 3D TV doesn't work. As near as I can tell all the electronics

are fine. I just missed one thing. Despite the fact that I can push out 120 FPS

to the LCD there's still a lag for the crystals to change (this is the "response

time" you might have seen advertised on your monitor). The timing on the little

LCD I installed is far greater than the 8 milliseconds needed. Maybe there's a

way around needing 120 FPS for the glasses, but I haven't exactly worked it out

yet. So far now the bits and pieces sit on my desk. A good idea and fun to do.

Close yes, but no cigar.

Comment on this post.