Packaging Software for the Pi

Packaging and distributing software for the Pi

Hamish Cunningham, October 2013

Contents

- 1. Introduction: the Good Old Days

- 2. The Problem

- 3. The Platform: GNU, Linux, Debian, Raspbian and Ubuntu

- 3.1. Ubuntu's Personal Package Archives

- 4. Debian Packaging

- 4.1. Creating the debian Directory

- 4.2. Conventions for the Makefile

- 4.3. Creating .deb and .dsc Files

- 5. Case Studies

- 5.1. SimBaMon and BlinkIP

- 5.2. WiringPi

- 6. The End

1. Introduction: the Good Old Days

Twenty-odd years ago I worked for a company building accounting and stock control systems for manufacturing businesses. I started as a general gopher, tea-maker and minor bug fixer on big old behemoths written in a language called COBOL — which some people claimed was a "common business-oriented language" but I was sure stood for "computer operators are boring and obviously lobotomised". Customers would phone up and say "we've got a new invoice format, can you change the report printer to fit?", and I would spend a day or two hunched over a stack of continuous paper (the type with perforated edges) with a special measuring ruler figuring out how many spaces to leave between the date and the address, and the like.

The low point of this phase was four days of my life spent chasing a rounding error in an invoicing program that resulted in a 2 pence error on a £10,000 invoice. I told the boss that I was happy to pay them the 2 pence every time it happenned if only I could stop leafing through that 100-page COBOL monstrosity1, but he didn't think that was a great customer relations strategy.

The company was starting to move into Unix-based delivery platforms (System V was the new thing back then; and a whole business would run on a tiny mini-computer!). I was lucky enough to get my hands dirty with the new technology, and learnt an awful lot in short space of time. It is a testament to the power and success of the Unix paradigm that I'm still using many of these skills today — C programming, shell scripting, systems administration and the like.

One of my tasks at the time was to package and distribute versions of our systems to customer machines. I used a program called UUCP (Unix-to-Unix copy) over dial-up modem links to push new updates onto machines out on site (and, cheekily, used to get the customer machine to phone us back so that the lengthy upload process would happen on their phone bill, not ours!). Things are a little simpler now: someone invented a thing called the Internet...2

The job of packaging and distribution continues to be important, though, and below I'll describe the mechanisms used for the Raspberry Pi's Raspbian operating system.

2. The Problem

Software packaging and distribution has to deal with versions, dependencies and access:

- Different versions of programs can incorporate lots of changes, including critical security fixes that need applying in a hurry. Especially on older systems and in low-bandwidth locations, minimising the amount of new download for a changed version is important.

- Dependencies between programs are often tied to particular versions — if a facility that one program relies on changes, the program's package data must reflect its need for the old version.

- Access to packages is relatively easy now — most software is distributed as a network download. But what happens if the connection drops half-way through? Or if a million people all want updates on the same day?

These issues have been addressed in various ways; one of the most succesful and wide-reaching is the Debian package management system, and this is the one that we'll describe here.

3. The Platform: GNU, Linux, Debian, Raspbian and Ubuntu

Debian is a distribution of GNU Linux, which is a Unix-like operating system (like Android, MacOS, Ubuntu, Red Hat and many others).

For the Pi there's a special version of Debian called Raspbian.

Probably the most popular version of Linux at present is Ubuntu, but because of an incompatibility between the Pi's version of its ARM microprocessor and the Ubuntu build system, we can't use Ubuntu's infrastructure on the Pi, except for programs which are architecture independent — a term which we'll explain below when we show how to use Ubuntu Personal Package Archives for Pi software distribution.

3.1. Ubuntu's Personal Package Archives

Broadly speaking, computer programming languages come in two sorts: compiled or interpreted. Compiled languages are translated into machine code (binary instruction sequences) before they can be run. Interpreted languages can be run directly without any translation. This means that programs written in interpreted languages are often architecture independent — they can run without change on many different types of computer chips. Several languages popular on the Pi fall into this category, including Shell Script and (with some restrictions) Python.

As we noted earlier, Ubuntu Linux is very popular (and is also derived from Debian). Ubuntu has a great set of infrastructure tools associated with it, including Personal Package Archives (PPAs) which simplify the task of building, packaging and distributing software for all the platforms supported by Ubuntu. If we're packaging an architecture-independent program, then, a PPA can be a good way to distribute it. (Several Pi GATE programs are distributed like this.)

Linux is open source free software, and to make sure everyone gets access to the source of programs in PPAs, Ubuntu only accepts Debian source packages as uploads to the archives. This means we have to build both a source (.dsc) and a binary (.deb) package for each program; the next section describes how we do this.

4. Debian Packaging

A lot has been written about packaging, and its fair to say that it isn't the easiest thing to get started with.3 We'll take a quick-and-dirty approach here, and give only enough detail for a couple of simple cases:

- scripts and other architecture-independent packages (including daemons, which are scripts run at system startup)

- binaries from compiled languages like C (including shared libraries)

In each case the key to the process is to

- create a debian directory in the top-level directory of your software tree, containing data to control the package construction process

- set up a Makefile in the same place which follows certain conventions for installation targets

The rest of this section describes these steps; in the next section we'll give example code.

4.1. Creating the debian Directory

The packaging file tree can be seeded using the dh_make program like this:

sudo apt-get install devscripts debhelper dh_make -p=package-name_1.0 --nativeThis creates a set of files in the debian directory, many of which are examples or boilerplate which can be ignored. The ones of the set that need editing in our cases are:

- control: contains the basic details of the package, its version and dependencies

- changelog: describes the changes present in each version

- copyright: describes the licence — this should be an open source licence

- docs: lists documentation files, e.g. a man page or a README for the software itself

- README: describes details of the packaging of the software, not the software itself

There is also a file called rules which follows Makefile syntax and which can be used to modify the details of the packaging process. In recent configurations this file uses a lot of implicit rules and doesn't need any changes.

4.2. Conventions for the Makefile

Having created our debian file tree we then need to create (or adapt) a top-level Makefile so that it:

- has a default target (e.g. all) which does any necessary compilation and linking of the software (for scripts this target probably does nothing)

- has an install target which adapts to the setting of a DESTDIR (destination directory) environment variable

The second of these is best accomplished using the install program. For example, given a binary called amazing, we can install it to DESTDIR from our Makefile like this:

install -d -m 755 $(DESTDIR)/usr/bin install -m 755 amazing $(DESTDIR)/usr/binHere the first command makes sure that the target installation directory (/usr/bin) exists; the second copies the binary file and gives it appropriate permissions for an executable program.

It is also convenient to wrap up the commands relating to packaging in Makefile targets; the next section describes these commands.

4.3. Creating .deb and .dsc Files

As noted earlier, the outputs from the packaging process are files of two types:

- .deb files contain binary builds of a program, which is all ready to install on a running instance of Raspbian

- .dsc files contain the source code of a program, ready to be built

We'll create these files using the debuild program. In common with several other packaging commands, debuild uses various helper programs to do its work. One of the disadvantages of this arrangement is that documentation is often spread across several locations. For example, the manual for debuild doesn't describe all of the options that it is parameterised by — some of them are only described by the helper program documentation. A good place to start looking for their meaning is in the documentation for dpkg-buildpackage (which in turn calls a whole team of other helpers).

The debuild commands that we need are these:

debuild -S -Ipackage debuild -IpackageThe first command builds only a .dsc source package (using the -S option). The second builds both a .dsc and a .deb. In both cases we ignore the package directory (via the -Ipackage option) as this is where we'll put the files generated by debuild.

We use the source-only build when we're targetting an Ubuntu PPA (see above) — these only accept source packages, building a .deb of their own from the source.

5. Case Studies

5.1. SimBaMon and BlinkIP

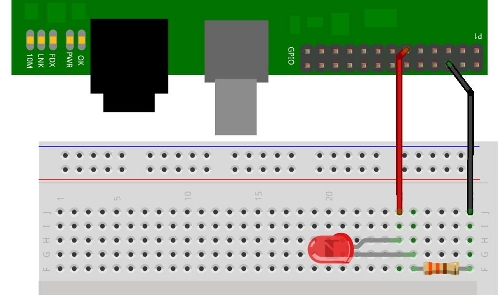

This section gives package file and Makefile code examples for the script programs described in our pages on the SimBaMon simple battery monitor and the Blink my IP daemons.

Below are summaries of the debian files used to build these packages. All of the code is on GitHub, including the Makefile.

The control file (the basic details of the package, its version and dependencies):

Source: simbamond

Section: admin

Priority: optional

Maintainer: Hamish Cunningham (http://gate.ac.uk/hamish/) <hamish@gate.ac.uk>

Build-Depends: debhelper (>= 8.0.0), devscripts, gawk

Standards-Version: 3.9.3

Homepage: http://pi.gate.ac.uk/pages/mopi.html#simbamon

Vcs-Git: git://github.com/hamishcunningham/pi-tronics.git

Vcs-Browser: https://github.com/hamishcunningham/pi-tronics/tree/master/simbamon

Package: simbamond

Architecture: all

Depends: bc, ${misc:Depends}

Recommends: gpio

Description: SimBaMon, a Simple Battery Monitor

SimBaMon is an open source Linux daemon for monitoring battery levels;

...

See http://pi.gate.ac.uk/pages/mopi.html#simbamon

The changelog file (the changes present in each version):

simbamond (1.3) unstable; urgency=low * Snapshot releases in the 1.3+4 series. -- Hamish Cunningham (http://gate.ac.uk/hamish/) <hamish@gate.ac.uk> Tue, 17 Sep 2013 13:44:00 +0100 ... simbamond (1.0) unstable; urgency=low * Initial Release. -- Hamish Cunningham (http://gate.ac.uk/hamish/) <hamish@gate.ac.uk> Wed, 14 Aug 2013 10:25:02 +0300(Use the dch -i to add a new entry to changelog.)

The copyright file (the licence):

Format: http://dep.debian.net/deps/dep5 Upstream-Name: simbamon Source: https://github.com/hamishcunningham/pi-tronics/tree/master/simbamon Files: * Copyright: 2013 Hamish Cunningham <hamish@gate.ac.uk> License: GPL-3.0+ Files: debian/* Copyright: 2013 Hamish Cunningham <hamish@gate.ac.uk> License: GPL-3.0+ License: GPL-3.0+ This program is free software: you can redistribute it and/or modify ...

The docs file (listing documentation files):

man/simbamond.txt README.txt

The README file (details of the packaging of the software):

The Debian Package simbamond ---------------------------- Comments regarding the package: - seeded using dh_make -p=simbamond_1.0 --native - adapted using instructions in the maint-guide package -- Hamish Cunningham <hamish@gate.ac.uk> Sat, 10 Aug 2013 18:51:23 +0300

There are a couple more files needed for SimBaMon and BlinkIP that relate to their role as daemons — see postinst, postrm and the .default and .init links in the debian directory.

5.2. WiringPi

A lot of our recent projects have used the excellent WiringPi library to talk to the Pi's electronics from software. A small frustration in this process has been the library's lack of integration into Raspbian... So I've written the code needed to do this, and made it available from GitHub.

Now we can install WiringPi without having to download or compile it, like this:

wget https://raw.github.com/hamishcunningham/wiringpi/master/package/2.13/unstable/wiringpi_2.13_armhf.deb sudo dpkg -i ./wiringpi_2.13_armhf.debUnlike the script-based examples in the previous section, WiringPi is written in the C programming language and therefore needs to be compiled before use. Gordon Henderson (WiringPi's author) uses a script called build to do this; to create a .deb I added a Makefile that copies code from the build script and adds an install target and packaging targets (like those used in the previous section).

Then I documented the other changes I needed to make (mainly adding the debian directory) and sent the details back to Gordon. Hopefully he'll pull them into his Git repository one of these days and start the process of getting WiringPi included in the official Raspbian distribution.

For reference and to give a flavour of the process, below are the details of the changes made to the library.

Most of the changes that I needed to make (as opposed to adding new stuff) are in this commit: https://github.com/hamishcunningham/wiringpi/commit/707cf1bc343e07c9c07eb67c55ed93873c2c67c8

All the changes needed are as follows:

- I've added a top-level Makefile which does some of what the build script does (just building and installing the two libraries and the gpio command at present). I believe that the build script still works as it used to. The package has to be built on the Pi itself; I tried cross-compiling but didn't get far :-(

- In the library Makefiles this line assumes that the binary has been written into DESTDIR, without PREFIX: @ln -sf $(DESTDIR)$(PREFIX)/lib/libwiringPiDev.so.$(VERSION) $(DESTDIR)/lib/libwiringPiDev.so. This doesn't seem to be the case, however... so I've added a PREFIX. Perhaps I've missed something about how make should be invoked, or...?

- The package build process requires that DESTDIR is used for everything — so calling "ldconfig" without parameterising it for DESTDIR causes an error. I've changed it to use DESTDIR for now, and also called ldconfig in the .deb's postinst and postrm scripts. This broke the build script's install, so I added this hack to the library Makefiles: @if [ x$(DESTDIR) = x/usr ]; then ldconfig; fi

- The devLib/Makefile does a -I., but this doesn't pick up the headers in DESTDIR, so I've changed INCLUDE there to do so (in the same way the gpio/Makefile does).

- The gpio build needs the core library to be built first, so I've put both the bare "make" and the "make install" under the top-level "install" target. Probably non-optimal.

- I have changed the gpio install to use the "install" command, which doesn't assume that the process is running as root.

- The .deb installs into /usr instead of /usr/local; I believe that Debian mandates that the latter is reserved for a "local administrator" or similar. The examples builds still work without change to the -I or -L flags as /usr is included in the default paths, it seems.

- I have added a compressed version of the man page, as that seems to be expected. I've also made it install the man page in /usr/share as that's the normal place on Debian. That might want parameterising in "build" if you want it to target other operating systems. Doing "man gpio" works but complains about lacking the .1 file; no idea why :-(

- I added an "install from .deb" para to the INSTALL file.

6. The End

Here endeth the lesson. Debian packaging is a bit of a black art, but with a little effort (and a lot of copying from our elders and betters!) the results are very powerful, stable and long-lasting solutions to the problems of software distribution and installation. Now it's your turn ;-)

Footnotes

- The program is engraved on my soul — it was called SOP-1, for Sales Order Processing, and it had grown and grown far beyond the ability of a neophyte like myself to ever understand. Trial and error was my only weapon, and it was a definite trial with lots of errors.

- The Internet, of course, mostly runs on Unix-based operating systems, as does your Pi, Android phones, and Apple computers.

- There are several reasons why packaging is hard. Debian is a distribution of code largely produced by other projects, so the packaging documentation often assumes that we're starting from someone else's systems, whereas in our case that's not true. Its design also dates back to a time where disk space and network bandwidth were very limited and it was important to split systems down into very small chunks stored on different disk partitions, problems that are less acute today. Nevertheless the original designers did such a good job that it's still the best there is. Kudos.